LOE Modeling Conundrum

Reserve Reports are for NPV, don't confuse them with cash flow models

In response to one of my Twitter threads, Mr. Shellman, long-time oilman and resident shale skeptic, posted the above post from Laura Freeman (and sorry Mike I don’t know who she is!). Essentially, this illustrates a common occurrence in reserve valuations, and that is modeling LOE on a single-well basis only with economic limits. I’ll not go into the accounting-specific issues she mentions, but obviously this does exist. Still, this isn’t a shale-only issue, it’s more of a marginal-producing well issue.

Anyway, allow me to explain…

The Well

First, as in most every industry in the world, operating expenses are composed of some combination of fixed and variable expenses. And even individual components have some sort of fixed/variable mix, though it’ll sometimes skew heavy one way or another.

Chemicals? For the most part this is driven by total fluid volume so you’d think largely a variable expense. Pumper? Mostly fixed. Compressor rental? Fixed. You get the point. These well-level expenses, with enough history, can be estimated reasonably (and assuming you can actually do your job).

Generally, once the well can no longer cover these expenses, the operator shuts it in and then has X # of years to P&A it. And X varies by jurisdiction. Nice, simple, easy.

In my ARIES or phdWin model, I can just schedule the well to produce to the economic limit and be done.

And that’s it, thanks for tuning in

.

.

.

Just kidding. If only it were so simple. In real life, there are a few things that make this a more difficult endeavor.

P&A

Lease

Field-Level Expenses

P&A

Theoretically an operator will shut-in the well once it no longer covers its’ cost. However, this rarely happens. Operators tend to produce these wells until they are no longer able to produce, and a lot of the reason is that they just simply don’t want to P&A well.

The cost of P&A’ing the well can be quite high, think somewhere between 50,000 and A LOT more than that, depending on how difficult the job is. So, it makes sense that they’d continue producing a marginally uneconomic well if they can put off this cost (and recall the P&A ticker starts once the well is done).

It also removes price optionality, as maybe oil moons to $200, all of a sudden that marginally uneconomic well is actually a good little producer. Once you abandon that thing, bye-bye option.

Lease

There is also that pesky ol’ lease. Could be you’re sitting on some nice juicy future Wolfcamp horizontal drilling that you’ve been deferring since the lease is Held By Production. Operators don’t want to take the risk that they will lose the lease, so will justify negative cash flows in the event the rig is needed elsewhere or that the economics of the future horizontals are sub-par but may work at much higher prices.

Field-Level Expenses

Onshore US wells for some reason tend to be modeled as stand-alone widgets. Me coming from an offshore GoM background, that was always a bit confusing. Platforms tend to be modeled as more of a hub-and-spoke, with the platform absorbing all of the fixed costs and the wells taking the variable.

In reality, onshore US wells act similarly. An operator usually has a field/lease with wells that are in close proximity. They likely share a compressor, tanks, and a pumper. There’s likely a field office somewhere. They’d be well served to model these with a “Field” case that absorbs some of these costs that largely stays flat over time, though has some step changes lower as well count drops to certain thresholds.

And sometimes that happens, but for the vast majority of models I’d see in banking or when evaluating a transaction, they’d stick to the widget.

Which is incorrect.

The Model

As is usually the case, a single-well valuation model is more or less the standard when it comes to the reserve report. Within each case, the analyst/engineer actually builds out the components of a DCF model, from well production to revenue/prices, ownership interests, capex, and opex. Honestly, for some reason someone along the way decided to give reservoir engineers ownership of something they really have no clue about (Economics!).

At least, it’s not covered too in depth in engineering school. That is one of the reasons I do advocate for some additional learning for reservoir engineers, whether through an MBA or something else, so that they can learn the impact of the decisions they are making with regards to their model. Expecting them to grasp the minutia of Managerial Accounting may not have been our best decision as an industry.

For some pesky reason, you’ll tend to notice that these models are missing low on production but high on expenses. If you rely on a Reserve Report-generated cash flow for your financial model (at least in the banking/M&A context), you’ll be sorely mistaken.

Now, caveat here, I have generally found the big boys internal models do a fairly good job of getting the model correct, and it’s because they have more than one owner of the inputs (ie their is a financial analyst working with the engineers to develop their field models).

Anyway, the default for these models is to produce them to the economic limit and then the software just assumes once well-level cash flow goes negative, the well is shut in and then a P&A is added like 5 years down the road.

Which, maybe theoretically is how it goes but as I mentioned above, is rarely what actually happens. That field office out in BFE Texas may be carrying like 100k or more in costs per year, and you’re allocating a small fraction of that to each individual well as opposed to building a field opex case.

Now, I can just wax poetic about the issues, but let’s run a though experiment.

Experiment

I’m going to build a simple DCF case using 1000 wells drilled over a 10-year period. To be lazy, I’ll just assume:

Texas well that produces ~50 MBO of oil over 30-year lifespan with a B-factor of 0.8 and final producing rate of 10 bbl/month.

2% Ad Val

$50/bbl WTI

Variable Expenses of $4/bbl of oil (who cares if it’s wrong, it’s just a dumb theoretical model).

$1000/month in fixed operating expenses per well

A field case of $1 million per month in expenses.

75% NRI and 100%WI

Valuation as of end of drilling program (ie 10 years)

In both cases, wells are produced to economic limit, but in one the field expense is attributed to the wells

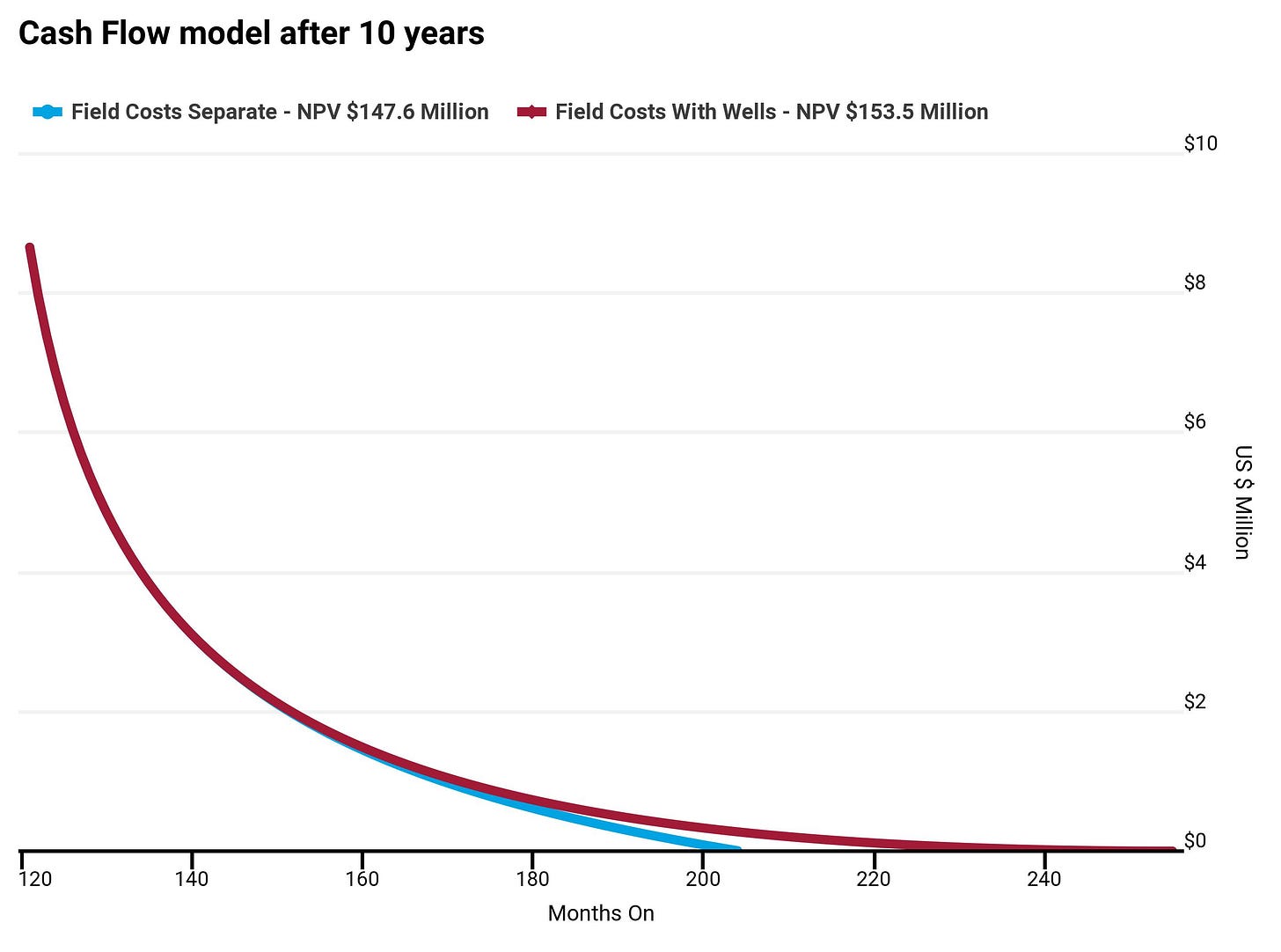

What do we see in both scenarios? Interestingly enough, overall cash flows aren’t massively different, though the model with the fixed field costs burdening the wells has a longer life. By burdening the wells with the fixed costs, we do see around a 5% bump in total NPV. In real life with a field closer to end of life with high variable expenses, you can see massive differences in NPV using this methodology (think at the 180 month mark in the below graph).

Of course, the real disparity occurs in the components of this cash flow.

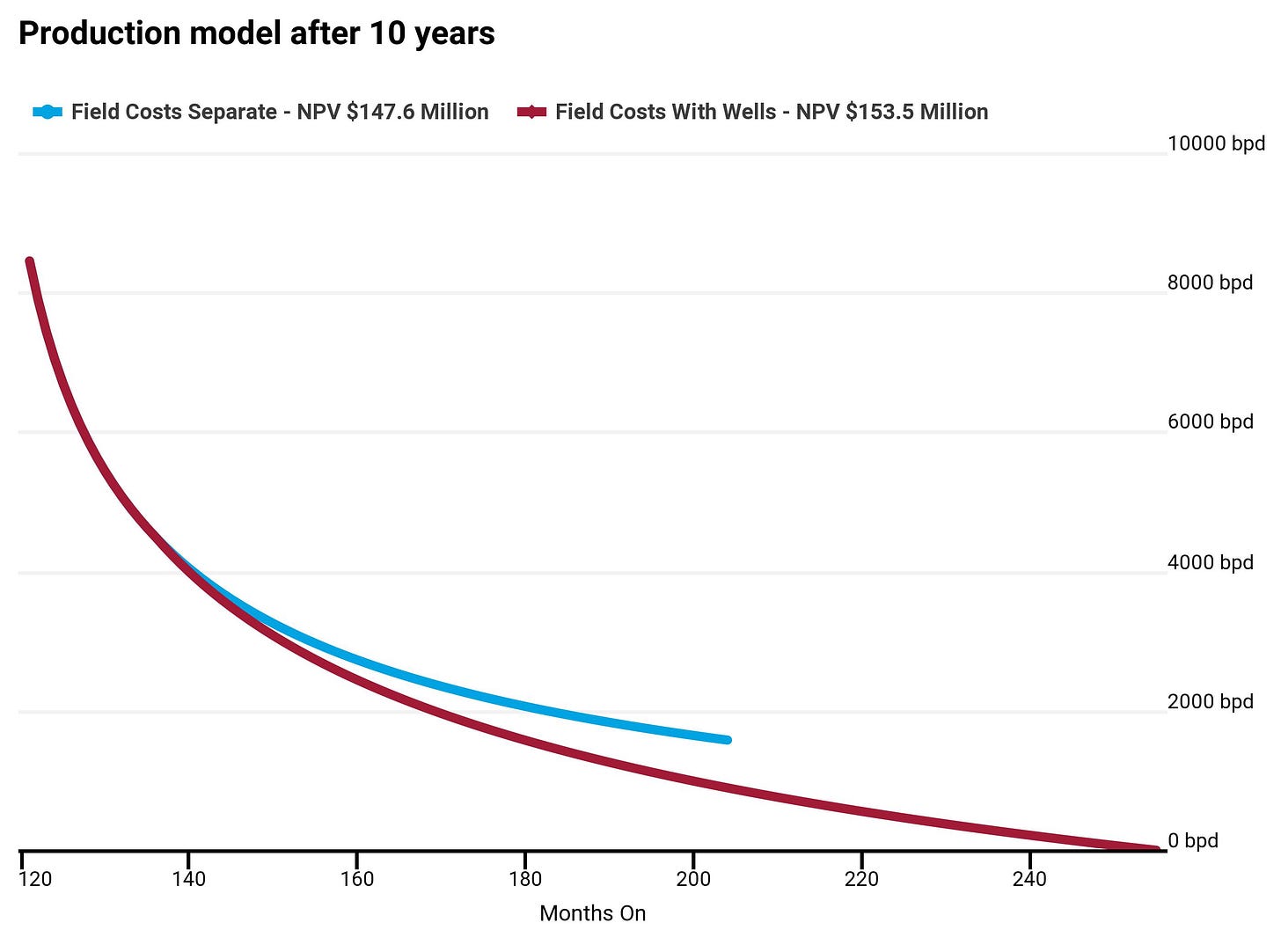

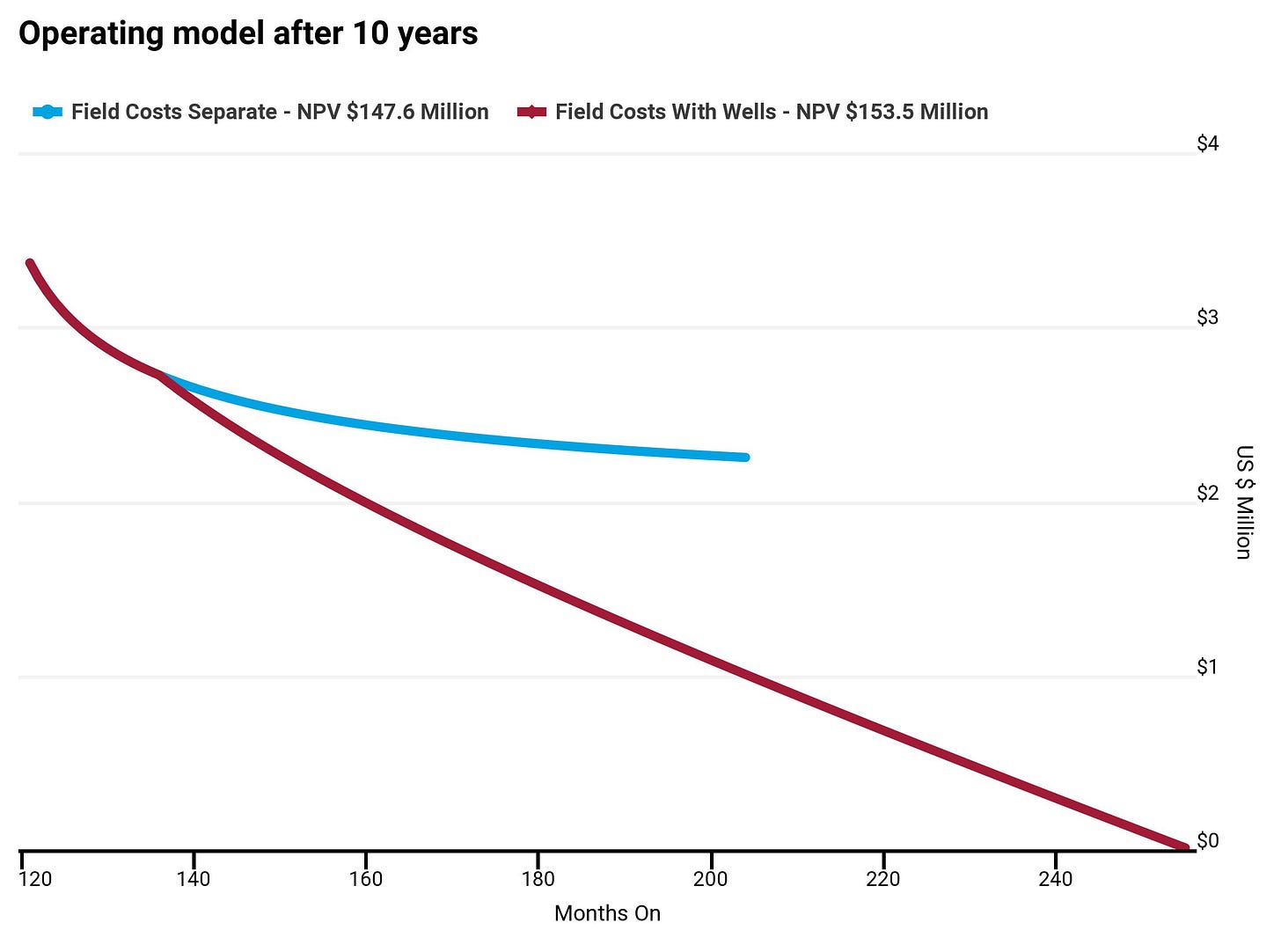

Production in our lower cash flow case is actually exceeding the other case, until, well, it isn’t. That’s because overall cash flow goes negative so the field is “shut-in”. So if that’s the case, revenue is higher, but our miss must be very large on overall LOE.

And that is a HUGE discrepancy. This is a perfect example of what I was referring to earlier in regards to reserve report models having a tendency to beat on production but miss on opex. This dynamic is occurring regularly, and in some cases the NPV impact is massive.

So what is the fix?

Generally, there are two options within the model.

Proceed with as is, but allow negative cash flows and produce the wells out to your modelled total well life. Of course, if you have a really huge dog well, that approach would need some customization.

Create the fixed field case and remove a load of the individual costs from the well. I tend to like this approach because you can hard-code various costs, like the compressor, or the field office, etc. to that single field case, and then the well is modeled similar to how the actual lease operator thinks about it in the field (ie if it’s covering my variable costs I’m going to keep producing this thing).

Of course, we can do things in the model to get the NPV closer in our case, or to represent actual field operations. For example, you’d have to assume a step-change in fixed field costs at some point once there are a lot fewer wells, so maybe you assume 25% savings on that fixed case once the well count drops below half. It’d need to be quantified, but there are ways.

BOTTOMLINE: Don’t rely on the reserve report someone provides as any sort of volume/opex predictor. It is an NPV tool only and does not represent real life.

Open to comments below on things you’ve also seen, but this is generally my experience in US onshore in regards to trying to figure out what the hell is going on when there are big mismatches between someone’s model and the actual cash flows/volumes.